Please do not forget the edge!

How did Cologne get onto the international art map in the middle of the Adenauer era? Thanks to the private initiative of Mary Bauermeister, you find out right at the beginning of the labyrinthine tour. She converted her studio at Lintgasse 28 into an anarchic playground for the Fluxus movement. This is where the original cell met before being awarded the label at the first official Fluxus Festival in Wiesbaden in 1962. Nam June Paik, Christo, Joseph Beuys, Merce Cunnigham and many others came to the experimental concerts and performances, attracted by the progressive profile of WDR, which caused an international furore with its studio for electronic art.

After a concert in the broadcasting hall, a visit to Mary Bauermeister's attic flat was a must for any aesthetically open-minded reformer. The trained double bassist Ben Patterson also performed here. The US-American came to the cathedral city to learn electronic composition from Stockhausen, but did not expect to meet John Cage, who converted him to chance music. He was able to perform some of his compositions in Wuppertal at the Galerie Parnass, but with little success. In 1962, he organised the Wiesbaden Fluxus Festival with George Maciunas, but remained an outsider in the white-dominated art scene.

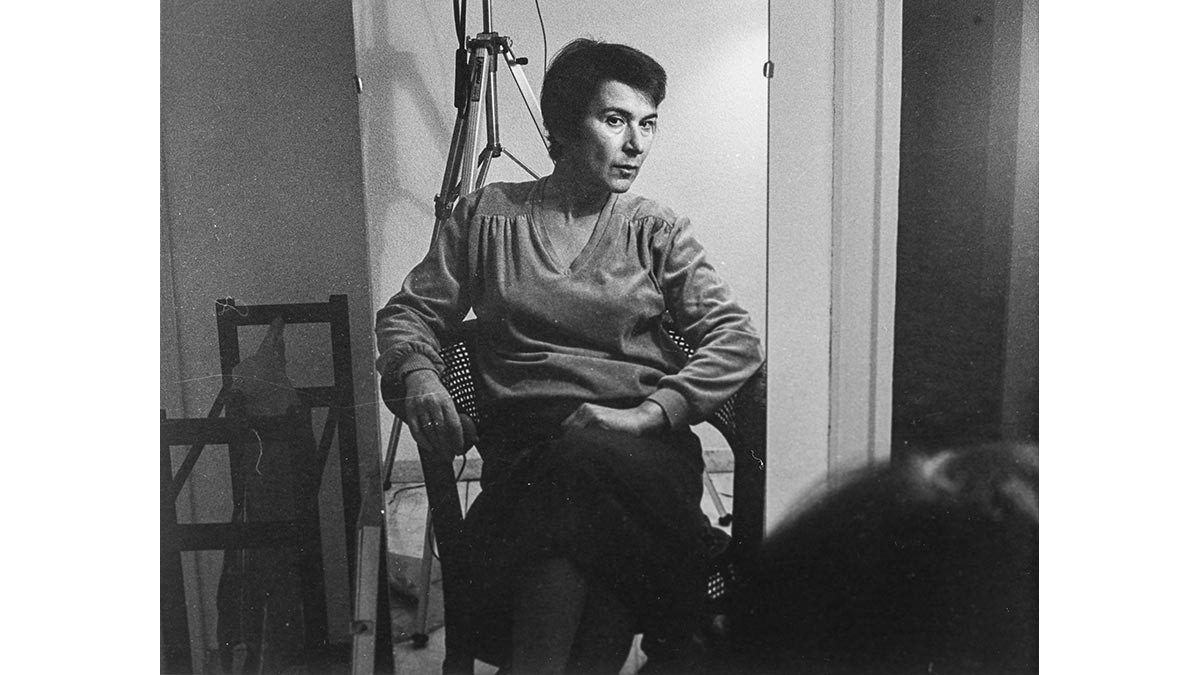

Ursula Burghardt in a self-portrait from 1981. Photo: © Künstler:innenarchiv of Stiftung Kunstfonds, Estate of Ursula Burghardt

Radical community experiences

It was a similar story for the sculptor Ursula Burghardt, the second protagonist of the exhibition curated by Barbara Engelbach. Born in Halle an der Saale to Jewish parents who fled to South America to escape the Nazis, she came to Cologne with her husband, the composer Mauricio Kagel, after she had stopped making abstract wooden sculptures because she found them too conventional. She began to explore the possibilities of metal and took an evening course in oxyacetylene welding.

Patterson and Burghardt met at Bauermeister's in 1960 and from then on worked on expanding the classical concept of art through radical communal experiences. What Dada had demonstrated at the beginning of the 20th century was suddenly topical again. Music took centre stage, for example when pianos were dismembered in front of an enraged audience. Destructive fun was just as much a part of Cologne's Fluxus as exuberant performances in private homes, which can be studied on countless black and white photographic wallpapers. In front of them are display cases with composition sketches, flanked by objects from the chance workshop of George Brecht, Wolf Vostell and Daniel Spoerri. They were shown in 1961 in the house of architect Peter Neufert alongside a sculpture by Burghardt and a shooting action in the name of Niki de Saint Phalle.

Attention through donations

The artist and musician Benjamin Patterson in 1989. Photo: © Wolfgang Träger

But why bring Burghardt and Patterson, of all people, two footnotes of this turbulent time, to the forefront? ‘Our museum is closely linked to Fluxus, not just Pop Art,’ says Director Yilmaz Dziewior. It was only through additional purchases, including from the collection of the former head restorer of the Ludwig Museum, Wolfgang Hahn, that these two artists came to the fore again. ‘Some of Burghardt's works were donated to the Kunststiftung am Museum Ludwig by Deborah and Pamela Kagel in 2009. In 2022, we acquired a series of works by Patterson with a view to the exhibition.’ The duo is also interesting because of their experiences of discrimination in the old Federal Republic. For Burghardt, the denial of his own perpetration, which was not uncommon in post-war society, was a burden. Patterson experienced racism in the rejection of his relationship with Pyla and also as a representative of the American allies.

Burghardt's Fluxus period is represented by the set design for a Beethoven film. Fictitious rooms of the Beethoven House were to be designed for the 1970 WDR production. She built a living room with petty bourgeois furniture, which she covered with aluminium sheeting. The silvery material elevated the room to a glamorous world, in which a man's shirt made of aluminium can also be found. It bears the slogan of the Persil company, a reference to the clean-washing certificates of exoneration after 1945. Her voice fell silent in the 1970s. It was not until the early 1980s that she returned with figurative drawings.

Patterson's retreat lasted two decades. In 1963, he returned to New York from Paris, where he had explored text and image in the ‘Puzzle Poems’ in several gallery exhibitions, and worked in classical music management. In 1985, he teamed up with the Schüppenhauer Gallery in Cologne and put on a performance for which he led Cologne residents through the streets blindfolded and with noisy cans tied to their ankles. Unlike most Fluxus participants, he did not shy away from bringing politics into play. He came up with a biting collage of briefcases on the CDU's black money affair. With his travelling museum of the unconscious, he later made guest appearances in Namibia and Israel, both key sites of German crimes.