Doubts on the home front

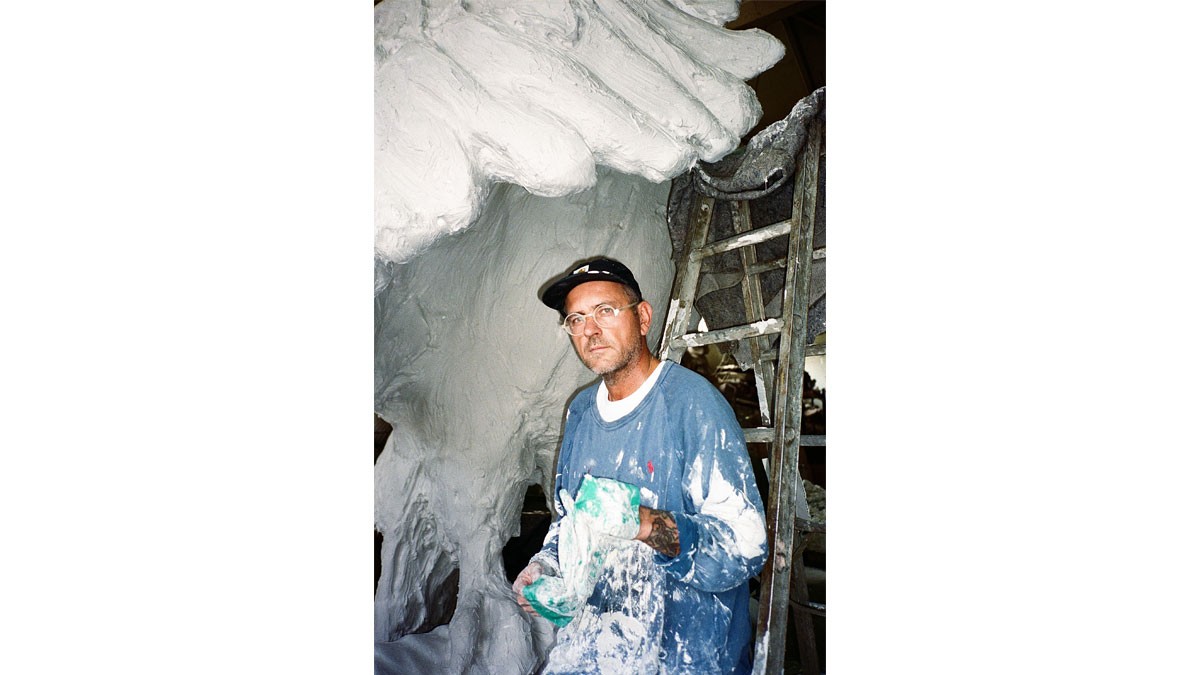

Stefan Strumbel's art has undergone a striking transformation. The 46-year-old artist from Offenburg first gained recognition with his alienated cuckoo clocks. Initially staged in a garish manner, these Black Forest icons struck a chord during the rapid globalization of the 1990s – as ironic symbols of home that could mark both belonging and exclusion.

These were joined by works such as sculptures wrapped in bubble wrap and canvases cast in aluminum. Media attention grew, and in 2010, the New York Times reported on him. Soon, personalities such as Karl Lagerfeld and Hubert Burda were among his buyers. Public commissions followed – for example, for the Stuttgart Opera and the 300th anniversary of the city of Karlsruhe, for which he created a bronze sculpture in the form of a chair resting on a tree stump.

Bronze has become Stefan Strumbel's preferred material – here is his sculpture ‘Hangover’ from 2025. Photo: Leo Suhm

Karl Lagerfeld and Hubert Burda as buyers

Strumbel, who is represented by Galerie Ruttkowski;68 with locations in Cologne, Düsseldorf, New York, Paris, and Bochum, is now increasingly focusing on sculptural works. His preferred material is bronze. In a new series of works, he draws on animal figures from his home region—not as folkloric references, but as ciphers for social and political conditions. The animals appear on fragments of cuckoo clocks, that symbol of Baden craftsmanship and identity, which is deconstructed and transformed here. What once represented home becomes a stage for fragile narratives of loss, change, and resistance.

Stefan Strumbel became famous for his artificial cuckoo clocks, such as this one, ‘Fox before Twelve’ from 2024. Photo: Leo Suhm

An eagle shows responsibility

The theme of animals and the material bronze now also come together in a sculpture that Stefan Strumbel created for the entrance to ART COLOGNE. And it is a highly symbolic animal that Strumbel has chosen—the eagle as a symbol of strength and national power. But Strumbel's eagle is different: it hides its face with its wing, silent, perhaps ashamed. Standing on the cone of a cuckoo clock, a symbol of home and tradition, it represents repetition and unreflective history.

Strumbel's bronze sculpture is not intended to be a proud monument, but rather an image of doubt, remembrance, and responsibility. The gesture of concealment remains ambiguous: shame about the past? Grief over the present? A clear “Not in my name” against hatred and exclusion? In this way, Strumbel deconstructs the eagle from a monument into a memorial. Its presence serves as a warning: homeland must not exclude, tradition must not blind. And symbols must be questioned, especially when they have so often been misused by the right wing.

Author: Alexandra Wach