An Indoor Garden All to Yourself

Are plants related to humans?

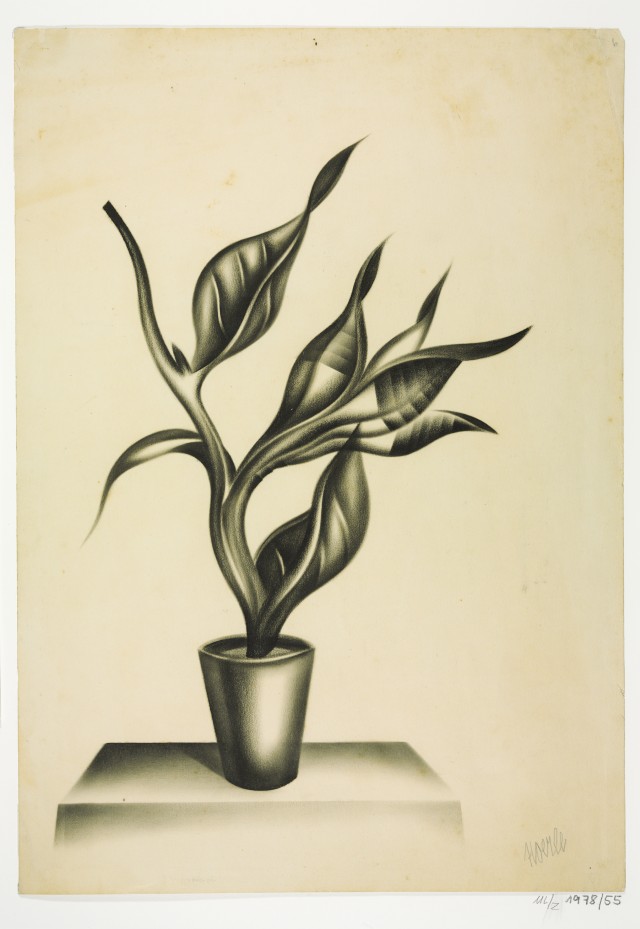

Credit: Museum Ludwig, Cologne | Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln/Britta Schlier/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022

In the 1920s and 1930s, this question was not only on the minds of scientists. The Comedian Harmonists had a profound friendship with a cactus, a plant cultivated in the Patagonian region of Argentina and in the Yucatan in Mexico for the German market. Otto Dix painted his wife Martha in floral dresses, holding a red-blossomed plant in her hands, while Hans Arp gave his sculpture “Knospenkranz” feminine contours. Karl Schmidt-Rottluff, apparently considering human beings to be overrated, painted a portrait of a delphinium in a window.

The new architecture of the Bauhaus preferred light-flooded windows, giving rise to the phenomenon of the “indoor garden.” The exotic thus found its way into the private sphere, and it was still women, despite all the efforts to achieve emancipation, who took care of the plants. Countless photos show them posing wearing their hair bobs, in a tender embrace with a flowerpot.

The dawn of a new age

Even in interior design magazines, tubular-steel furniture accompanied cacti and rubber trees, and not vice versa. And Marlene Dietrich, who liked to wear trousers and tails, winkingly signaled her affiliation with the female sex, which was just taking possession of male attributes, with a huge carnation in her buttonhole. These are just a few of the variations on a relationship that had become fluid in a technology-obsessed era in which people desperately wanted to be progressive and sought refuge from their own excesses in the world of plants.

Das Blumenwunder, 1926 (Filmstill) Regie: Max Reichmann | Credit: absolut Medien GmbH, www.absolutmedien.de

In the exhibition “Green Modernism. The New View of Plants,” which is on view in Cologne until January 22, 2023, 130 exhibits provide an informed and entertaining account of the dawn of a new age. The photographer Karl Blossfeldt, for example, was not looking for a green friend, but for material to study the forms of leaves, buds, and stems, which he achieved by means of extreme enlargement. City dwellers went dancing in “tropical ballrooms” and flocked to cinemas to study the “aliveness” of their potted plants in the film “Blumenwunder,” shot using the then popular time-lapse photography.

Heinrich Hoerle, Topfpflanze (Pot plant), 1920s | Credit: Museum Ludwig, Cologne / Reproduction: Rheinisches Bildarchiv Köln

And lo and behold, the wunderkind subsequently even became a flesh-eating bio-monster in horror films such as Murnau’s “Nosferatu - A Symphony of Horror.” A hundred years later, the climate crisis dominates our view of flora and fauna. People grow their own fruit and vegetables, and artists like Olafur Eliasson write vegan cookbooks.

The trend doesn't stop at curators, and the show was realized without loans and transports. The catalogue is only available digitally, but free of charge. Even the museum restaurant is participating. Pumpkins from the museum’s own roof terrace are used for dishes on the menu. The pilot project in sustainable exhibiting does not lose sight of any detail and thus evokes a coexistence on which today’s humans are more dependent than ever before.

Text: Alexandra Wach